Page 3 of 7 pages

Previous Page

Next Page

(Interview with Jack Wolcott, continued)

-

L.C.: Tell us about the technical aspects, the hardware and software you used or developed. I know you had some grants from IBM. Did other companies

support you as well?

JRW: Between 1984 and 1992, IBM was very much involved. They provided equipment, some software, and lots of technical advice. The IBM grant, called The Olympus Project at the University of Washington, was administered by Dr. Greg Zick and Steve Graham, his administrative coordinator. Funds were allocated annually, and the allocation was competitive. We had to submit a progress report every year, and demonstrate the work that we had done. A peer review committee then decided whether to continue the grant or take away the applicant's computer and give it to someone more productive. The model for this, I think, was Nicholas Negroponte's computer and video "Media Lab" at M.I.T.

We in the theatre department had many needs that extended well beyond a computer on a desk top: scanners and plotters, video capture equipment, cameras and VCR's; laser disk players. No money had been allocated for equipment such as this, so we begged, borrowed and cajoled. The Intel Corporation, for example, let us beta test one of their first video capture cards, and a local distributor loaned us a high-end plotter for one of our projects. My academic department, once it became clear that I was often spending money from my own pocket for software and equipment, began to provide some small financial support, and the university administration stepped in from time to time to reward some of our more interesting achievements. Our success with the IBM project continued to put newer and more powerful computers into our laboratory.

Software companies took special interest in our work, primarily because we put their products to uses that they had never imagined. As an example, Constant Lu, a young undergraduate I hired in the summer of 1986, discovered that an instructional software package called Quest® contained coding that provided for rudimentary animation. By summer's end, Mr. Lu had developed a library of figures which, when combined, enabled a "character" on the screen to walk down a flight of steps, growing larger as he approached the viewer, and "characters" which could sit, stand and walk about the screen. We used these figures, in conjunction with a laser disk of Orson Wells' Citizen Kane, to illustrate concepts of stage composition and choreography.

IBM asked us to beta test a wonderful software package called Storyboard®. This was designed to do simple "if-then-else" branching, but we put it to an unexpected use when the second version, which could handle graphics, was published. Our analysis of Florimène, the 17th century English court masque, was developed by undergraduate students using Storyboard 2®. The Florimène software is still in use world-wide today, nearly fifteen years later.

|

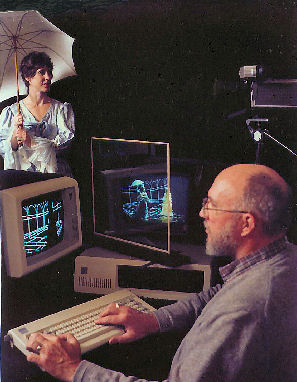

One experiment that attracted a great deal of attention at IBM and the University of Washington involved a beam splitter - similar to so-called "one way glass" that is

often found in police interrogation rooms and psychology clinics. Using the beam splitter, two monitors and a video camera, we were able to create the illusion that live

actors were performing on a computer generated three-dimensional stage setting. While the optical characteristics of this project excited great interest, the use of 3D CADD

(Computer Assisted Drafting and Design) software was more exciting still to us.

This was in 1986 and 1987, and other than for main frame computers there were very few CADD programs of any kind on the market. Ironically, the software, which was a prototype, had many features still not found in CADD programs today. The developer suffered a nervous breakdown trying to work out problems in the software, and was retired from the game. His software was never marketed commercially after that. Sometime later, a software company located near the University of Washington began publishing a program called Generic CADD(tm), and soon followed this with Generic 3DD(tm). These were exceptional drafting programs and, for the first time, gave us tools with which we could approach architectural and technical drafting and modeling. One of our first projects with Generic 3DD(tm) was the modeling of the Hellenistic Theatre site at Pergamon. This combined working with the 3D CADD software and a plotter table, extruding the archaeological site map into a measured three dimensional model. We continued working closely with the developers at Generic for the next several years. L.C.: What kind of feedback did you receive from the University at the beginning? JRW: This was very interesting, like sweet and sour pork. On the sweet side, the faculty and administrators involved with The Olympus Project were enthusiastic enough that they continued to support our work throughout the duration of the project. Since continued support was competitive, I interpreted this as a sign that we were productive and worthy. On the sour side, few of my colleagues in the theatre had any interest in the work, those in theatre history and in technical theatre least of all. Interestingly, among theatre historians this continues to be true today, 15 years later. |

|