There's No Business Like Show Business:

Shooting and Editing Live Theatre |

| © 2003 by Jack Wolcott |

Shooting theatrical events can be a lucrative enterprise for event videographers, especially if they pay attention to the unique demands of the theatre and to sound business practices.

When my wife Judy started her video production company several years ago, she gave up a prosperous career of forty years as a theatrical lighting designer. My own work in the theatre as a stage manager and director began in the early 1950s, and after many years at the University of Washington, much spent in research developing theatrical tapes and laser discs, I joined Judy in her company in 1998. Not surprisingly, we are often called upon by the Seattle theatre community to video tape theatrical works ranging from new plays to performances by international musical, dance and theatrical troupes at the Seattle International Children's Festival each year.

Event and wedding videographers have to shift gears mentally to become good theatrical videographers. Theatrical videography isn't about photojournalism, although you'll often hear from the client that "I just want a record of the production." Sometimes this is to be taken at face value: a one camera shoot with no editing. What this usually means, however, is that the client wants you not only to record the actors walking around on the stage in front of the scenery and under the stage lighting, but to capture the emotional essence and nuances of the work as well. For the videographer this means finding a way to mediate between the creative components of a theatre piece and those of video.

Theatrical Conventions

Three factors weigh heavily in creating an event on the stage:

- composition

- focus

- picturization.

Composition involves the arrangement of elements on the stage - actors, scenic pieces and furniture, light and shadow - into aesthetically pleasing pictures that change from moment to moment as the play progresses. Composition has been referred to as "rational arrangement . . . to achieve an instinctively satisfying clarity and beauty." (Dean and Carra, Fundamentals of Play Directing; 1980, p. 100)

One of the goals of composition is to control focus: in other words, to make sure that as we sit in the audience we are looking at whoever or whatever on stage is important at the moment. Unlike film, where the viewer is constrained to look at a specific action on the screen, the theatre's stage may contain multiple simultaneous actions, only one of which is of paramount importance. For example, the setting might be a living room, with a man mixing drinks on one side of the stage while a couple argues heatedly on the other. Are we to watch the bartender or the couple? Unless the intensity of the action and the stage composition directs our attention to the focal point of the scene, we're free to watch either or, for that matter, to watch the lights above our heads in the auditorium.

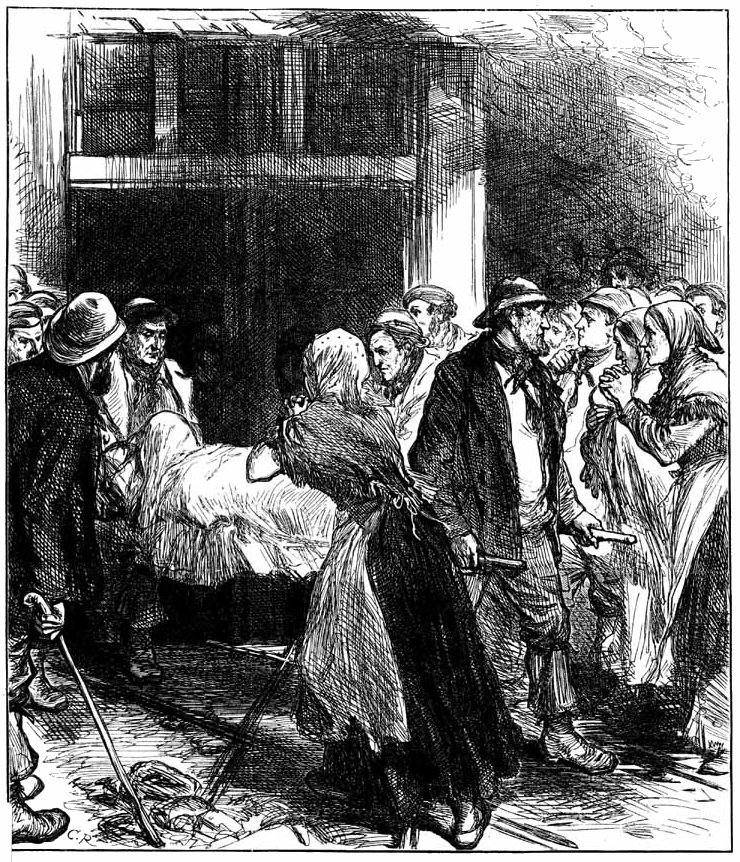

Composition is about the arrangement of stage elements. Picturization, on the other hand, is about meaning, about telling the story without words, bringing us understanding through what we see. We don't need to have a verbal account of the events in the 19th century drawing in Figure 1 to understand the horror it depicts and the relationship of the onlookers to the dead man. The shrouded figure on the stretcher, the tension in the body of the woman standing at the left-hand foot of the stretcher, peering toward the reclining figure's head; the spectators leaning in to get a look at the body, faces grief stricken; the woman at the right-hand edge of the picture, her hands intertwined in prayer, all speak to the disaster that this drawing portrays. (The Illustrated London News, Saturday April 28, 1877)

Figure 1

Composition and picturization compliment each other. The figure on the left holds a walking stick, whose tip nearly intersects a dark line leading up to the woman at the end of the stretcher. Her body leans in toward the head of the dead man; the upward inclination of his head carries our eye upward to the stretcher bearer who looks not at the deceased but at the grieving woman at the foot of the stretcher, clearly the most important figure in the drawing. Line in the composition moves our eye through the picture, causing us to consider each element.

The figure carrying the foot of the stretcher plays an equally important role compositionally. His vertical mass separates the principals from the onlookers. Moreover, rather than looking straight ahead, which would lead our eye out of the frame of the picture, he looks to his left, at the woman whose hands are clenched in prayer. She and the two people to her right appear to be looking at the woman who leans in at the top right of the stretcher, peering at the deceased. This woman's focus inward carries our eye back to the head of the deceased and from there to the stretcher bearer and back to the grieving woman at the foot of the stretcher. Elements in the composition work reciprocally: start anywhere in the picture and the eye is led eventually to the shrouded corpse and back to the mourner.

So picturization and composition work hand in hand. The challenge facing the videographer is to recognize the interplay between the theatrical elements of composition, focus and picturization and accommodate them in his shot selections, which of necessity are often only portions of the larger stage picture.

Developing a Shooting Strategy

Attempts to translate stage performance to film began early in the 20th century. In 1912 Louis Mercanton filmed Sarah Bernhardt in Queen Elizabeth, placing the camera in the center of the auditorium and using a cover (wide) shot which encompassed the entire proscenium for most of the piece. Unfortunately this created two problems. Much of what happened on stage couldn't be seen, the camera being too far removed, and the very aspects that makes film - and by extension video -- such a powerful medium was denied as well: the close-up and the reaction shot.

To go beyond Mercanton's approach and capture the essence of the theatrical production that the client hopes to see in the completed video we must start by attending a dress rehearsal of the production, being certain that the theatre's staff and the play's artists and technicians know ahead of time that we'll be there.

The goal at the dress rehearsal is two-fold: to establish a working relationship with those who will be running things on the day of your shoot, and to resolve some of the technical and artistic problems inherent in any theatrical shoot. It pays to arrive at the dress rehearsal a couple of hours early. Introduce yourself to the house technical staff and to the production's stage manger. These are the people who control the workings of the venue and the production, and their knowledge and help will prove invaluable. Find out from them whether there's anything special you need to know about where you can set up your equipment and whether there are special things you should know about the production, such as actors working in the aisles of the auditorium, unusual lighting and sound, scenes that may be difficult to shoot because of their placement on the stage. The stage manager will be able to give you an idea of how long each act lasts, important information with regard to changing tapes during performance.

Scout your camera locations, power sources, cable paths and the location of the loading dock, nearest rest rooms and coffee shop. Determine how early you can get access to the theatre on the day of the shoot. Find out the name of the house manager, the person responsible for safety and traffic flow in the auditorium. Your equipment will be set up in this person's domain, and it's important to achieve instant rapport on the day of the shoot. If you think there might be a problem, call the house manager ahead of time.

Set up a camera, find the audio technician and get plugged into the house board to test levels during the rehearsal. Make sure you know what pot you've been patched into, what its level is, and how it relates to the board setup as a whole. This will give you an opportunity to verify that you have all the cables and connectors necessary to patch into the house board, as well as to hear what the show mix will sound like.

Unless you intend to set microphones for the show yourself, which in many theatres isn't feasible, make it a contractual matter that the theatre company's audio person, and not you, is responsible for the audio quality of the finished video piece. Be sure to discuss this with the audio technician and the show's producer at the same time. This gives the audio tech a vested interest in giving you the best sound possible, and lets you off the hook if the audio is clipped or non-existent. Remember: if the audio is blown out when you record it from the board feed, it's very difficult or impossible to fix in post.

Camera Positions

Dealing with the artistic aspects of the shoot begins with establishing shooting positions. Your theatre shoot will probably be with two or perhaps three cameras, usually located at the rear of the theatre. At one time we used one unmanned camera, placed on the center line of the stage, for a cover shot of the entire stage, but found its footage to be almost useless, so we now shoot with just two manned cameras.

There are two considerations as to where your cameras are placed. The comfort and utility of the shooters is of greatest importance. Expect to be standing behind the camera for 90 minutes or more to record the first act of a typical contemporary play, 60 minutes or more to record the second act. Being wedged between seats, or into a tight corner of the auditorium, is unacceptable.

Ideally, set up cameras in the open area behind the last row of seats. This usually provides ample room in which to work. If we have to shoot from within the seating area, however, our minimum require is that three seats in each of two rows be reserved for each manned camera. The front legs of the tripod go in the row closest to the stage, the back leg in the row behind. Since it can be difficult to see into the camera's view finder, it's a good idea to use a monitor that can be set up on the lower row. Producers usually aren't happy about this arrangement, since it costs them the income from a dozen seats, so they'll usually do everything they can to avoid this being necessary.

The second consideration is aesthetic. It is an axiom of architectural photography that a quartering view of a building - that is, a view from the corner, that shows both the front and a side of the building - is more aesthetically pleasing than a photo taken from directly in front of the structure. The former is dynamic, implying the potential for movement from the front to the back of the building, while the latter represents the building as a wall, a barrier at right angles to the line of sight. The axiom holds true in theatrical photography as well: a shot along the axis of an "X" that crosses the stage from the footlights to the rear wall is inherently more interesting than one that is taken on the center line. With this in mind we try to place our cameras about a quarter to a third of the way in from the left and right edge of the stage. In many theatres this puts us just left or right of the top of the main aisles - house (auditorium) left and house right.

With the cameras in these positions, the conventions of theatrical staging serve to help theatrical videographers. In general, stage directors make every effort to keep actors "open," that is, to arrange them in such a way that most of the people in the audience can see the actor's face. This works best when the orientation of the scene is consonant with the "X" axes of the stage, orientation of the scene is consonant with the "X" axes of the stage, in an orientation such as we see in Figure 1. The videographers can then shoot "cross stage" - along one of the legs of the "X" axis -- as well as on their own side of the stage if the scene is sufficiently open to permit this.

Shot Selection

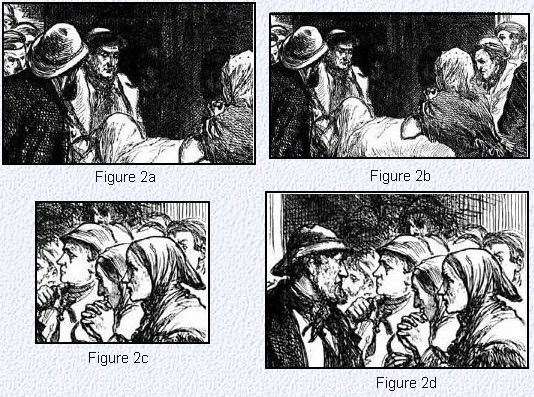

One of our jobs during the dress rehearsal is to familiarize ourselves with the play, deciding loosely how each scene in the play will be shot; whether, for example, the scene on the left side of the stage will be shot by the left camera or by the right. If the events depicted in Figure 1 were placed on stage, the scene would be on the audience's left hand side of the stage.audience's left hand side of the stage. Shooting the scene from the "house right" side - that is, from the right hand side of the auditorium -- would roughly align the axis of the camera with the axis of the stretcher, allowing for a clear shot of the action and permitting close-ups such as those in Figures 2a and 2b below. The figure on the extreme left of the composition would block most of the action for the house left camera, which could never-the-less get a fine close-up of the mourners, as seen in Figure 2c.

Back in the days of live-switched studio shoots, each camera operator had a stack of "shot cards," three by five cards strung together by a ring through the corner of each card, like paint chips. As soon as a camera was released by the director, the operator looked at his next shot card, repositioned the camera if necessary, and lined up the next shot.

In practice, without a director controlling cameras and calling shots, shot cards are of little value in theatre shoots. There is rarely a moment during the shooting of a play that cards or lists can be consulted. So in addition to discussing who's shooting what as we watch the rehearsal, we also address shot selection when we're shooting the production by running a cable from the output of one camera to a small monitor by the other camera. This enables us to ensure that the scene is always adequately covered: the videographer with the monitor always knows that the other camera is shooting and can adjust his or her shot accordingly, wide shot or close up.

What one person calls a close-up, of course, may be another's wide shot. Referring to Figure 1, for example, are we looking at a close-up or a wide shot? Since the stage is probably thirty five to forty feet wide, and we can imagine twenty other people on stage, I'd call it a close-up. When it's compared to Figure 2c, however, it's a wide shot. If Judy sees on the monitor that I have the shot in Figure 1, or for that matter the shots in Figure 2a and 2b, she knows it's safe to shoot Figure 2c, providing a beautiful cutaway for our edit.

The question of shot selection is tightly tied to picturization, and this is often the subject of considerable discussion as we watch the rehearsal. "What is this moment showing us," we ask. Figures 2a, b and c illustrate how a videographer might choose to shoot close-ups of the scene depicted in Figure 1. Why not use Figure 2d; it's part of the larger composition? Figure 2d, out of the context of the larger composition, however, picturizes a different story: it's about three women who appear to be imploring a gruff looking man. Not an ideal cut-away.

Stage Lighting and the Video Camera

Stage lighting rarely presents conditions that work to the videographer's advantage, and perhaps the most important issue to be dealt with during the dress rehearsal concerns aperture settings for the cameras. There are several schools of though regarding how to handle exposure. One method is to set the camera on "auto" and let it run. If we do this with our PD-150s, and it's true with other cameras as well, there is often so much light on stage that the image is completely blown out, especially if there is a heavy use of follow spots.

Another method is to manually change the iris settings throughout the production. There are two drawbacks to this approach. Cameras like the PD-150 have click stops for each iris setting, making changes very obvious and extremely time consuming to deal with in post production. Moreover, there is a tendency among those who chose this method to flatten out the stage lighting, making the lighting in each scene look like its predecessor. It makes for good profiles on a wave form monitor, but really doesn't capture the lighting moods of the performance. And if it's overdone, adjustments to the iris create the sense that the stage lights are continually dimming up and down.

A third method, which we have found produces excellent results from the theatre people's point of view, is to determine a single optimum setting for the entire production. We shoot the brightest scenes early in the dress rehearsal at several f-stops and with close attention to the camera's zebra bars, logging each change of setting for future reference. Using a monitor and the zebra bars we find the setting that appears to work best for these bright scenes - lets say f/stop 4.8 We then shoot some of the darker scenes in the play, using the f-4.8 setting and settings that bracket it - f/stop 4.0 and 5.6 for example.

Once we have found a couple of settings that enable us to capture the quality of the lighting on stage, we shoot several scenes of 3-5 minutes at each setting. Back in the studio we can compare these - we use an MX-50 set up with a split screen - and decide which setting to use throughout the entire performance. We then decide on a setting that will work for the entire play and set up the cameras for the performance shoot. The look may be quite different from what we'd expect to see if we were shooting the production under studio lighting conditions, but what we're looking for is the artistry of the stage lighting rather than video that meets broadcast specifications.

Post Rehearsal Consultation

Following the dress rehearsal it's imperative to meet with the director and producer of the show and discuss special considerations that you have seen during the rehearsal. Don't rely on asking a director before the dress rehearsal "what do you want emphasized." Case in point: A production came into town from New York City to try out new material; no chance for us to see a rehearsal. About thirty minutes before the shoot we met with the director, who said "don't shoot the scenery, just focus on the dancers." So we did. Ten minutes after he received the tape in the mail he called: "You've ruined the whole thing. You didn't shoot the banners when they flew in." Had we been able to see a rehearsal and then meet with the director, we would have had a lengthy discussion about the banners which, even as we were shooting, we felt played a much more important role in the production than the director's cavalier pre-shoot comment suggested.

And it's in this after rehearsal discussion that matters concerning picturization can be discussed with the director. Remember: you're concerned with what you can see in your view finder while the stage director must deal with a stage space thirty five to forty feet in width and perhaps twenty feet deep. Is it important that we see the kids playing on the left side of the stage, twenty feet away from the two lovers? Dealing with questions such as this before you shoot can avoid the often heard "Gee, I wish you had included (fill in the blank) in your shot. That's what the whole scene was about."

Tips for the Day of the Shoot

Safety must be your number one concern as you set up to shoot the performance. Not only will patrons stream in to the auditorium around your equipment, but quite often they will be moving around after the lights in the auditorium have been turned out. When setting up tripods in a theatre, remember Murphy's law: anyone that can bump into your tripod will. Try to position tripods so that the legs do not touch any of the seats. If at the rear of the auditorium, place unused gear under the tripod, as close to the legs as possible. This gives the tripod area mass, and avoids the likelihood of a patron tripping over a leg. Once the audience begins to enter the auditorium, stand next to the tripods. It's a small price to pay to avoid having an expensive camera knocked over, and it also discourages theft as well.

Cables should be run parallel to the flow of traffic as much as possible, and should be taped down with yellow gaffer's tape for security and visibility. Don't use duct tape. It leave a residue on carpets and floors, and will make you very unpopular with the theatre staff. An alternative to taping down cables which may be appropriate in heavy traffic areas is a flexible cable cover, such as those shown at cableorganizer.com. Tape it down well, too.

Check with the house board operator as soon as possible after you arrive to set up. You'll want to verify that things are set up the same way on the day you shoot the performance as they were at the dress rehearsal. Ask for a sound check and have the operator play a CD at the highest volume he expects to have on his board. Make sure he gives you plenty of head room. Ask if anything in the audio for the show has changed.

Ask the house manager - the person in charge of the ushers and seating -- if there will be any sort of announcements made prior to the start of the performance that should be included on your tape, and ask for at least a couple of programs. Take good care of these. The cover of the program makes an excellent graphic to open the edited tape or DVD, a graphic which may be contractually required by the copyright holder - as in the case of Les MisÚrables, for example. The program also proves invaluable in post for the cast and crew credit roll. Also find out from the house manager when the audience will begin coming in.

Perhaps the most important requirement for successful theatrical shooting is consistency. Develop a routine and stick to it. Everything in its place, and always in the same place.

You're always working in near total darkness when shooting in the theatre, so hang a small flash light on the tripod. The back of the auditorium can be one of the darkest places on earth should you have an equipment emergency or need to change tapes.

Put spare tapes into your pocket, and get into the habit of putting them in the same pocket every shoot. Nothing is worse than trying to locate a tape for a quick change that has been knocked to the floor or is in the clutter of your camera gear.

Label tapes for each act with the show name, the date, the act number and the shooter's initials. Black the first thirty seconds of each tape. If you're shooting with miniDV cameras always use different length tapes in the cameras. Start with a 63 minute tape in the camera whose output goes to the monitor. Then, when it's time to change this tape, the camera with the longer tape is still shooting, the operator can see that the short-tape camera is off line and can pull back to cover the scene while the other changes tape.

When you remove the tape from your camera, slide open the "Save" tab immediately, then put the tape into the appropriate pocket. It only adds a few seconds to the tape change and prevents any possibility of mistakenly reusing the tape in the dark, of losing it and of having it stolen. Never, ever leave recorded tapes in the open or in your gear bags.

Copyright and Releases

Besides the aesthetics of shooting theatrical material and the nuts and bolts of handling the shoot, there are several business considerations that must be dealt with. The issue of permissions is of paramount importance. Plays and musicals are protected by copyright. There is absolutely no gray area here, no "fair use" or "just for fun - we're a non-profit group." Permission to perform plays and musicals is a contractual matter arranged between the copyright holder - usually the author or his or her agent -- and the Producer. The terms under which they may be performed is specified in the contract, and these terms usually include whether or not the work may be recorded by any electronic means and whether the right to broadcast is granted.

The Producer also enters into contractual agreements with any artists who are members of the theatrical performance and craft unions, as well as with members of the musician's union who may be employed in the performance. These agreements are usually very specific with regard to videotaping, audio recording and broadcasting of performances.

So whether or not it is legal to videotape the play is an issue that lies in the contract between the copyright holder and the performance and craft unions on the one hand, and the Producer on the other. You have no role in the permission process.

But that doesn't absolve you from responsibility. When we created our contract for theatrical shoots we addressed the issue of liability with our attorney. The advice I remember most was this: "You can't bury your head in the sand." In other words, ask your client (the Producer) if he has obtained the necessary permissions. If he says "yes," it's probably alright to go ahead with the video taping. However, if you have doubts ask the Producer for a copy of the contracts which give him this permission. If you're still in doubt, walk away from the job.

We make responsibility for obtaining permissions a contractual matter between our company and the Producer. At the very least we can say that we were lied to should a problem arise. Here's how we've set up a section of our contract to handle this. How this is worded and the protection it affords is something each videographer should discuss with his or her attorney.

| Permission to video tape. |

| a. | Client represents and warrants that he/she has obtained necessary permission(s) to videotape this

production from copyright holders.______Client initial |

| b. | Client represents and warrants that he/she has obtained permission(s) to videotape this production from cast, musicians, crew members and others associated with this production, and from audience members who may appear incidentally in this videotape. _________Client initial |

| c. | Client agrees to indemnify VideOccasions in the event of any litigation arising from the videotaping of this production. ______Client Initial |

Payment

A final note of caution: be very careful when it comes to payment for your work. Theatrical production groups are often shadowy entities formed by an individual or ad hoc collection of actors that want to "do a show," but which are not a licensed business, have no permanent address and are usually under-funded. Having a video of the production seems like a great idea before the fact. Paying for it after a disappointing run is less appealing. Once the last performance closes, the Hamlet "company" you were dealing with ceases to exist. The actors go on to other work, the Producer goes back to his day job. If you're not careful, you can wind up doing a great deal of work and not getting paid.

Basing your fee on the projected sale of tapes and DVDs is courting disaster. Instead, calculate your costs for shooting, editing and tape and DVD duplication, mark up for your overhead and profit and charge that figure. If the Producer wants to resell the tapes and DVDs at a marked up price, that's his business.

In calculating your costs, remember that you've spent four to five hours in the dress rehearsal. On the day of the shoot you'll put in at least another four. From the point of view of time invested it's beginning to look like a wedding, and can take nearly as long to edit. A four or five hundred dollar theatrical shoot is a charitable contribution to the arts, not a business transaction. Get paid for the shoot before the performance begins, and paid for the editing before releasing any tapes or DVDs. Don't trust the Producer who says "Just let me have a tape so the cast can see it, and then I'll bring you their orders for tapes and DVDs." Copying is too easy. You're welcome to anything in the box of unclaimed show tapes and DVDs that taught us this lesson.

Shooting theatrical events is challenging and rewarding. One well produced theatrical tape can bring in calls from theatrical groups throughout the state. There really is no business like Show Business!