"Drawn During Representation:" Fact or Fiction?

The discussion which follows is the work of Mark Farley, a PhD student in the University of Washington, Seattle Washington. It examines the theatres in which the plays were performed, and the evidence which links Pierce Egan the Younger's engravings to the playhouses.

Five engravings from plays in the University of Washington collection and a single engraving reprinted by Raymond Mander and Joe Mitchenson [Mander, Raymond and Joe Mitchenson Lost Theatres of London London: The New English Library, 1976. pp. 186 and 112] appear to be accurate depictions of the prosceniums of theatres visited by Pierce Egan the Younger. This accuracy has been corroborated by examining prints and engravings of these theatres by other artists.

The Theatres and the Drawings

| The St. James | Royal Olympic |

| Theatre Royal Haymarket | Theatre Royal Drury Lane |

The St. James Theatre

The British Legion,*

|

The St. James opened on December 14, 1835 under the management of John Braham. Braham operated the theatre until 1840 when he and his wife went bankrupt. The theatre was then

re-opened as the Prince's Theatre for two years before closing again and reopening as the St. James under the management of John Mitchell. The theatre underwent an extensive

renovation in 1900. It remained open under a variety of managers until it was demolished in 1957.

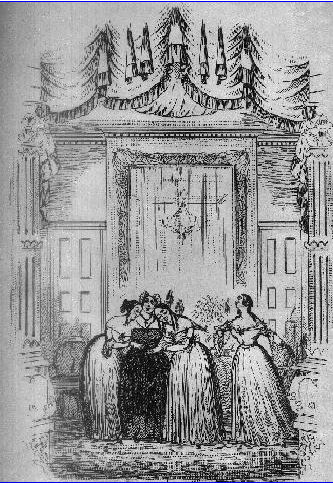

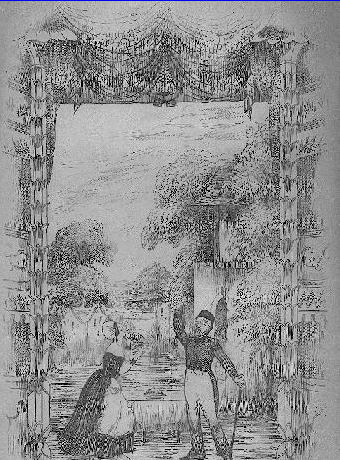

Egan's engraving for The British Legion shows the theatre in it's first (1835) incarnation. The interior architecture of the St. James theatre was unique among theatres of it's day. The building was designed by Samuel Beasley, and featured just two tiers of boxes, making the seating capacity about 1200, relatively small compared to other West-End theatres. Egan's drawing of the St. James shows the distinctive columns that served as the frame of the proscenium. As a contemporary account (1836) in the Morning Herald states: The lower part of the proscenium consists of a rich entablature, ornamented with trusses and swags of flowers, supported by fluted columns, with intersecting enrichments, and splendid gilt capitals resting on carved pedistals. *As you can see, Egan clearly represented these columns, resting on their carved pedestals. This evidence is further corroborated a watercolor drawing done in 1865. Which shows the interior of the theatre (it was not remodelled until 1869). This watercolor* shows two columns stacked on top of one another on each side of the stage. Where the two columns meet, there is a capital decorated with wavy lines, and there is a more flambouyant corinthian capital on the top. This watercolor also shows the rounded pedestal that supports the columns, as well as the flat stone area which supports the pedistal. Also, the watercolor shows the "drapery" at the top of the stage which was not a drapery at all, but a carved wooden piece. Egan's drawing for the British Legion shows all of these architectural features, but they are "squished" to fit into the frame with the actors. The columns and the pedestals are significantly shorter and fatter than their corresponding representations in the watercolor, and Egan's version of the ornamental drapery looks very similar and contains the same number of folds, but its vertical dimensions have been "squished." Egan's drawing actually corroborates parts of the newspaper reporter's description that the watercolor does not. Egan shows the floral patterns that were supposedly carved into the pedestals and which accented the columns, which are too small and detailed to be included in a watercolor.

|

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane

Our Mary Anne*

|

Drury Lane was one of the most popular and influential theatres in the nineteenth century. In Egan's time, the theatre was in its Fourth incarnation. Following the extremely successful

partnership between Edmund Kean and Robert Elliston, the theatre was

remodelled in 1821, and kept the same appearance (the decorative, horn shaped, embellishment on the proscenium) until the 1890's. In Egan's time, the theatre had a capacity of 3060.

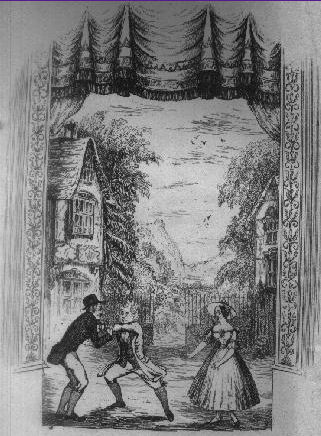

Egan's engraving of J.B. Buckstone's Our Mary Anne at Drury Lane is less informative than his drawing of the St. James, but it still shows a number of architectural features that mark it as a clear represntation of Drury Lane in the 1830s. The interior was remodeled in 1831 and remained quite unchanged until a major renovation in 1847 *. A watercolor*, painted in 1842, shows the interior to be quite similar to the way that Egan has drawn it. The watercolor clearly depicts the horn shaped design on the border of the proscenium, as well as the relatively flat line of the drape which adorned the top of the curtain. The watercolor also reveals that the design which Egan draws at the bottom of the the drape is, in actuality a series of gold colored tassels which serve as the fringe for a bright crimson curtain, which, according to an article in The Builder are of the same material "of which our army officers' uniforms are made" *. Another distinctive feature shared by both the watercolor and Egan's drawing is the point where the pattern on the proscenium end as it intersects a pedestal about 3-4 feet above the stage floor. As in the other pictures Egan has, of course, altered the dimensions of the theatre he is showing. Though the decorations on the proscenium are actually relatively close to being the proper scale when compared to the actors, the two sides of the proscenium are far too close together (the proscenium of this version of Drury Lane was over 40 feet wide *). Also, the drape at the top of the stage, though generally accurate, is shortened along its horizontal axis so that it fits the picture.

|

The Royal Olympic Theatre

The Two Figaros * |

The Theatre's HistoryIn 1831, Madame Eliza Vestris took over the Royal Olympic Theatre and made it into one of the most fashionable theatres in the 1830s. She was the first woman theatre manager in London. In 1835 Vestris' troupe was joined by actor Charles Mathews, and they soon became London's most recognized stage couple. Vestris and Mathews were married three years later (although he was significantly younger than she.)The Royal Olympic Theatre was the site of numerous theatrical innovations including the sideways parting curtain, fast scene changes, and the first box sets in London. Vestris often worked closely with playwright J.R. Planche, who actually took over managment of the theatre during a highly unprofitable tour of New York in 1838. Vestris and Mathews closed the Olympic in 1893 when the chance arose for them to take control of the lease of the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden. The financial strain of the New York tour and the move to a larger theatre eventually led them to bankruptcy. The theatre was remodeled in 1849, and demolished in 1889. It was then rebuilt in 1890 and lasted another 15 years before being torn down for the final time in 1905.

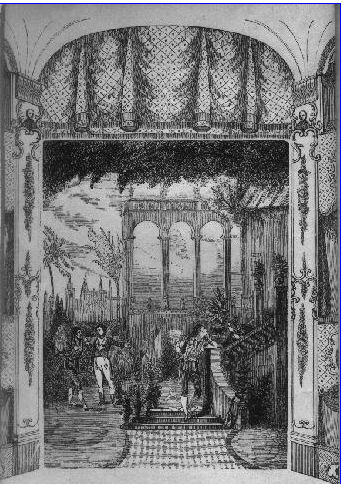

About Pierce Egan's IllustrationsEgan's drawing for the Two Figaros and The Ringdoves, shown below, are important historically because they appear to be the only surviving visual evidence of the Royal OlympicTheatre during the Madam Vestris era (1831-1839). To these drawings may be added the Egan drawing of J.R. Planche's Court Favor, also from the 1830's, cited by Raymond Mander and Joe Mitchenson as one of the only remaining depictions of the Olympic's interior in the 1830's. *In his introduction to The Victorian Theatre, 1792-1914, George Rowell concur, noting that

Little evidence of the scenic reforms of Madame Vestris and Charles Mathews has survived. The scene from Court Favor by J.R. Planche . . .claims to be 'an engraving by Pierce Egan the Younger, from a drawing taken during the representation' . . . Mathews and Madame Vestris are recognizable in the parts of David Brown and Lucy. * |

The Ringdoves*

|

Although all three of these historians thought it likely that Egan's drawing was done in the theatre, it is my hope that research currently undertaken will further substantiate this claim.

There are two Egan engravings of plays at the Olympic in our collection, The Two Figaros and The Ringdoves. Both exhibit similar prosceniums, made up of two decorative panels festooned with some sort of floral design in the center of each panel, and topped by an elaborate capital adorned with a representation of a human face, or what might possibly be interpreted as the face of a cupid.

These engravings, together with the engraving of Court Favor indicate that there are four objects set into each of the floral designs on the proscenium's panels. Although these objects vary in size and shape, they appear to be apples. In the engraving of Planche's Two Figaros, by far the most detailed of the three, the apples appear to be set into a clump of flowers rather than the four separate inlays depicted in the engraving for Charles Mathews' The Ringdoves.

Also, at the top of the proscenium in the engraving for Two Figaros there appears a very realistically drawn bust of a human man. The other engravings are less destinct, showing vaguely cherub-like shapes instead.

Finally, the drape at the top of the proscenium is almost identical in each engraving, suggesting that this was possibly made of wood rather than fabric.

Of the engravings, that of The Two Figaros appears to be most detailed and reliable, showing even the interior of the boxes in some detail. Given the relative accuracy of

Egan's other drawings, it is likely that the

We should not be mislead into thinking that Egan's engraving of the Olympic's proscenium heralds an Olympic Theatre play, however. By the 1840's Egan's engraving of the proscenium

for Two Figaros seems to have become a template for other

Webster & Co. engravers, at least two of whom used Egan's engraving to represent the proscenium of the Haymarket Theatre.

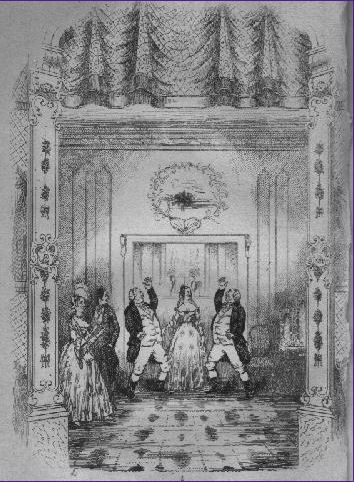

The Maid of Croissey*

The Theatre of the Egan's day was managed by Benjamin Webster. Egan shows the interior of the theatre as it looked from 1820 until it was remodelled in 1858.

*

Egan's Interior of the Theatre Royal, Haymarket is one of his most intriguing engravings. It is a picture of Benjamin Webster's (the publisher of the play) theatre. And it shows

an extremely distinctive proscenium,

The proscenium of the the Haymarket remained relatively unchanged throughout the 19th century, though the interior was remodeled several

times *.

A picture of the Haymarket, painted in 1821 shows several

distinctive features*. First, the drape at the top of the proscenium forms a flat horizontal line. Egan shows this flat line, as well as a slight indication of a drape in front

of the wooden structure (the entire drape might be a wooden construction).

The sides of the proscenium are decorated with a bizzare geometrical shapes which look like a series of flowers growing out of one another. Egan shows these "flowers" but, based on

the painting, he seems to show too many of them.

The picture also corroborates Egans drawing of the pedestal at the bottom of the proscenium, a double column with the same floral accents in place of capitals.

Both the painting and Egan's drawing also show the umbrella shaped capitals on the top of the proscenium, but the painting shows one more decorative "joint," (similar to the one between

the two segments of the pedestals at the bottom of the proscenium) just below the umbrella shape. Also, Egan does not seem to agree with the painter about the decorations on the boxes

(though the number of boxes is the same).

These discrepancies could be due to a rennovation of the interior in the 15 year period between the painting and Egan's drawing, but the interior is definately, and definatively the

Haymarket of the early 19th century.

The Theatre Royal, Haymarket

Mrs Charles Gore

Throughout the 18th century, The Haymarket served as the principle competition to the Patent houses. Hurt by the Licensing Act of 1737, which stripped

the theatre of it's licence, the Haymarket soon returned to prominence under the able leadership of George Colman the elder (1776).