| Dissolves and Cuts and the Language of Video |

| © 2002 by Jack Wolcott |

At the heart of communication, whether it's verbal or pictorial, are the concepts of conventions and language.

Convention: A rule, method or practice established by general consent or usage.

Language : Arbitrary symbols [used in] conventional ways with conventional meanings; any

set or system of such symbols as used in a more or less uniform fashion by a number

of people, who are thus enabled to communicate intelligibly with one another.

Conventions form the "language" of an art, whether theatre, film, video, painting and sculpture, even architecture, and this language has meaning. For example: perspective is the illusion of spatial depth on a flat surface. There are several conventions that we interpret when we see a perspective drawing: some objects are drawn to overlap others; some are drawn larger than others; and some are placed lower in the composition than others. Finally, parallel lines converge at the horizon.

We learn to read this visual language in childhood: overlapping objects are "closer;" larger objects are "closer;" objects lower in the composition are "closer." The convergence of parallel lines is associated with infinity, with distance. When these conventions are present in a drawing, we read them and assign the meaning "depth."

Recently, revisions were made to the New Collegiate Dictionary, and "noogie: a brisk and often painful rubbing of the head with knuckles" was officially added to the English language. The word, in use for decades, finally made it into the dictionary. Language is never static: the 16th century "aroint thee" gave way to "buzz off," and "ain't" has become an entry in every modern dictionary.

Like English, the language of film and video has changed over time and continues to change, perhaps for the better, perhaps not. Nowhere is the instability in the language of video to be seem more clearly than in the use of dissolves and cuts.

Background

Many film and video conventions developed from the stage. The first plays, written some 2500 years ago, were performed in large outdoor theatres during daylight hours. Scenes that were supposed to be taking place at night were indicated by the convention of having a character appear carrying a torch or lantern.

There was no way to draw a curtain in the outdoor theatres, and no artificial lights to dim: in other words, no way to indicate the end of a sequence of action or a change of place. So the convention developed that plays should take place in one locale, during a continuous period of time.

These conventions lasted, largely unchanged, until about 400 years ago when performances moved indoors where curtains could be rigged and artificial illumination -- candles and oil lamps at first -- began to be used. With the introduction of gas lighting and electric lighting in the 19th century, it became possible to dim the artificial lights - in film and video terms, literally to fade (dissolve) to black - to indicate the conclusion of a sequence of action or a change of place. Fading to black became associated with changing the scenery - that is, with the action moving to a new place -- or with indicating a passage of time. By the end of the 19th century this stage convention was understood throughout the western world.

Dissolves

Not surprisingly, The Great Train Robbery (1903), one of the earliest U.S. films, used theatrical conventions, associated with the language of the stage, to separate the scenes of the story line, dissolving (or dimming down) to black through the use of the camera's iris. When the iris opened again -- that is, when the film dissolved out of black into a picture -- the action was seen to have moved to a new locale. Films that followed used this convention in much the same way. Until recently, dissolves in both film and video signified a change in place or time. This meaning was part of the "language" of film, a convention so universally understood that when Oscar nominee film editor Thelma Schoonmaker chose to use a dissolve in a novel manner in The Age of Innocence (1993) it attracted the notice of film critics and writers alike.

Cinematographers and videographers often use the content of film - what is happening in the story - to create transitions that are synonymous in meaning with the dissolve. An airplane, rising from the runway and flying out of frame from left to right, leaving only empty sky, for example, is followed by a cut to similar empty sky and a similar airplane entering the empty frame from left to right and landing. The meaning that time has passed and a new location reached is communicated by the action of the airplane.

In 1965, the inaugural episode of TV's The Man from U.N.C.L.E. introduced a startling new substitution for the dissolve, the whip-pan. The whip-pan, which creates strong directionality by blurring the video image through a rapid panning motion, suggests a movement through space and time, figuratively a rapid turning of the head to look from New York toward Philadelphia. As used in U.N.C.L.E., this technique echoes the breathless quality of the show's storylines.

Transitions like the dissolve, the airplane fly-away and the whip-pan are attached to meaning: they further the narrative flow of the storyboard and extend the timeliness. With the introduction of digital video editing, however, the dissolve has been subsumed into "the transition" or "effect," and is used more or less indiscriminately, without regard for meaning. Today, dissolves and other transitional effects are often used to disguise bad video. Transitions are used instead of cuts between camera one and camera two, for example, because of inconsistencies in lighting and white balance between the two cameras, or because neither camera has a useable shot of the action and it is necessary to insert a shot of some other activity. It's interesting that we still think of this as a "cut away," rather than as a "dissolve away!"

Using a dissolve or other transition to move from shot to shot is often attributed to aesthetics: a transition is used because it is thought to be "softer," or "less jarring" than a cut, or because it provides movement in an otherwise static scene. Unfortunately, these transitions are disassociated from meaning. Clearly neither time nor place have changed, and the viewer is left to ponder what these transitions mean. Confusion reigns.

But there is hope. Two things have happened during the past 15 years that have changed the way we look at the world and understand what we see. To a certain extent, both involve how stories are told, or at least how information is communicated. Perhaps they will serve to guide us toward a new set of conventions involving dissolves and other transitions.

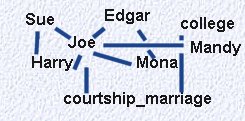

The first was the introduction of hypertext, seen most often today as links in text on the World Wide Web. Before hypertext, information was acquired in a linear manner, like reading a book, as seen in Figure 1.

Joe → his siblings → college years → Mandy → courtship → Marriage

Figure 1

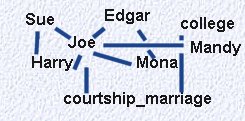

Hypertext, on the other hand, allows the reader to shape the narrative as he or she finds necessary or desirable. In Figure 2, it is possible to begin reading about Joe, pursue links to explore his family, discover Mandy, go straight to marriage and never read about their courtship; or go directly to Mandy and marriage, skipping everything else entirely.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Moreover, in a hypertextual universe time is omni directional. We can start with Joe and eventually get to Mandy, but we might also choose to start with Mandy, follow one of several branches, and eventually arrive at Joe, in terms of the linear narrative creating a "flashback." We could even begin with Sue, one of Joe's siblings, explore Joe's entire family, and never get to his wedding at all. (Richard L. Pryll, Jr.'s Lies was a wonderful example of omni directional hypertext narrative at its best. Unfortunately it has been removed from the WWW. 12/30/12)

Remember that at the heart of language is convention. It has taken a decade and a half for hypertext to become conventional - for people to have agreed on how it works and how to understand it. Few today are confused by links on the web. Where once we understood in a linear fashion, we can now understand in a multidirectional, multivalent fashion. At least two magazines currently on the news stands begin stories on the last page, page 90 lets say, and continue the story on pages 89 and 88 for readers who begin at the end of the publication and work forward!

The second shift in visual and perceptual language was led by Apple and Microsoft with their Graphical User Interfaces (GUI). Words were stripped from the computer workspace, substituted for by little pictures - icons. Some, such as the picture of a printer, were intuitive, while others had no intrinsic meaning. Here again, we have had to learn this new visual vocabulary, agree upon its meaning and add it to the visual language. Today, a question mark in a box has become the universal symbol for access to the Help menu.

Perhaps you're wondering by now what all of this has to do with dissolves and transitions? Consider the coverage of professional football. In network coverage of professional sports an attempt has been made to establish new vocabulary in the language of the dissolve, but as yet there seems to be no agreement as to meaning.

The game of football is linear, a narrative: play follows play, quarter follows quarter. That's how the game is seen in the stadium. It's old-fashioned, like reading a book. Television coverage of the game has become hypertextual, however. The linearity of the game is augmented by the introduction of "flashbacks," the ubiquitous replay. A play is shown multiple times, and from multiple angles, each replaying of the down separated by a "swoosh" of the network logo, or some other exotic effect. The effects are analogous to the computer's icons: no language is used to signal that we have moved backward or forward in time. Instead, the effect transition takes the place of commonly understood language to create a language of its own. Moreover, to follow the analogy of hypertext, we are pursuing multiple "links" that allow us to digress from the game narrative to create new and secondary narratives. Not uncommonly, these secondary narratives may take us out of the current game entirely, to see scenes from an earlier game. But little currently helps us to understand at what point we rejoin the game in real time.

We're left with a kind of linguistic chaos, with a well established convention, the dissolve and its associated transitions, being used in a new way that is not yet conventionalized. Nothing in the current vocabulary of video communicates what dissolves mean now, and the viewer is on his own to determine the significance. We can only hope that, like hypertext links and computer icons, this will coalesce into a new, coherent vocabulary.

Cuts

Like the dissolve, the ground work for the conventions and language of the cut in film and video was laid in the theatres of the 19th century, as the role of the theatrical director evolved. Dramatic content moved from swashbuckling melodramas to intense psychological studies of the development of character. Where the director of melodrama concerned himself with managing traffic on the stage - keeping sword fighters from bumping into the furniture and each other -- the director of late 19th century plays took great pains to focus the attention of the audience toward each speaker on the stage as complex psychological narratives unfolded. The bulk of Alexander Dean's early 20th century seminal treatise on stage directing (Fundamentals of Play Directing,) for example, deals with "focus," that is, on making certain that the audience is looking at each speaker on stage as he or she delivers their lines.

With the help of the stage director, the audience at a stage play makes metaphorical "cuts" from one character to another as the dialogs passes back and forth from character "A" to character "B." We turn our eyes from speaker to speaker, just as we would while watching a tennis match.

Film editors enabled us to keep our heads still by alternately substituting picture "A" and picture "B" on the screen. This gives the film maker, and by extension the video maker, an enormous amount of artistic control, since the audience is now forced to look at a the specific character, object or scene of the editor's choosing.

Imagine Mary and John seated at a table.

John : Mary, I love you. Will you be my wife?

Mary: I can't, John. My sordid past would only come between us.

John : Then I shall never see you again.

In the theatre, the audience is free to look at either character, at both, or at neither as this little scene plays out. But the film editor chooses what will be seen, and each choice directly affects how we derive meaning from the scene, how we understand the nuances and implications. The possibility for cuts in the just the first line of the scene above suggests the editor's power to control:

John: Mary, I love you. (Cut to Mary) Will you be my wife?

Or we might cut like this:

John: (CU of Mary, John's voice over) Mary, I love you. (Cut to John) Will you be my wife?

Or like this:

John: Mary I love you. Will you be my wife? (Cut to Mary)

In the first instance, we see John speak of his love for Mary, then cut to her reaction to his proposal. In the second our focus is entirely on Mary as she receives the declaration of love from an unseen speaker, then on John as he follows up with his proposal. In the third, Mary is not a visual factor until both the declaration and the proposal are completed, creating suspense as the viewer wonders what Mary's reaction will be.

With control comes responsibility. Not only do cuts enable us to see and understand actions and reactions, but cuts create meaning through montage, the juxtaposition or sequencing of images.

Imagine a wedding in which the mother and father of the bride are divorced and have both remarried. A particularly lengthy discussion of fidelity by the pastor suggests to the editor the need for some visual relief, so the editor looks for cut- aways of the congregation listening to the sermon.

| Pastor: |

". . . and remain faithful, one to the other. (VO: For it is written that

husband and wife . . . |

| |

[Cut to Mother and new Husband] |

| |

[Cut to Father and new Wife] |

| |

[Cut to Bride and Groom] |

| |

[Cut back to Pastor] |

| Pastor: |

. . . shall be wed throughout all eternity." |

Meaning that is generated here through montage is poetic and evocative. At one level the meaning in this example can be read with irony and skepticism: the parent's marriages didn't last, so why should we think the bride and groom's will? Another reading might be more hopeful and affirmative: even though the marriage of the mother and father failed, the Bride and Groom are starting out on a fresh journey, and we can hope for the happiness of which the Pastor speaks.

Cutting to the Action

Much is made of "cutting to the action." For many editors, this means cutting to movement, cutting as John begins to turn toward Mary, cutting back as Mary reaches out to return John's ring, cutting as John rises and rushes to the door.

There is another kind of action, however, far more subtle and far more powerful. Contemporary critical theory of film, video and theatre suggests that thought is action, even though there is no physical movement involved. To cut to thoughts as action the editor must find those places in a speech where the direction of ideas change, where there is "movement" in the thought process.

At a wedding, the priest selects this passage as his text:

1. Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not charity, I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal.

2. And though I have the gift of prophecy, and understand all mysteries, and all knowledge; and though I have all faith, so that I could remove mountains, and have not charity, I am nothing.

3. And though I bestow all my goods to feed the poor, and though I give my body to be burned, and have not charity, it profiteth me nothing. (I Corinthians 13, 1-3)

This one's easy: the breaks in the verse and the italicized phrases instruct us in our cutting. The first verse is about speaking, the second about understanding and faith, the third about giving and sacrifice. We may cut at the end of any verse, since each verse completes a "thought action." Letting the idea of montage guide our choice of images in cutting, we might open on the priest, cut to the statue of Isaiah the Prophet at the end of the first verse, cut to the Crucifix at the end of the second, and back to the priest at the conclusion of the third.

We could be more subtle still in our cutting, however. The disciple Paul uses a classic rhetorical form in these verses, which we can follow in cutting to the "thought actions." Each verse is constructed as an antithetical pair: "Without X, I am Y." So we could cut at the change in "thought action" within each verse: "Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, (cut?) and have not charity, (CUT) I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal." More possibilities here that we thought!

Sometimes it's difficult to determine where "thought actions" change, and where it's appropriate to cut. Bearing in mind that when and where we cut affects meaning, we may have several options, resulting in subtly or grossly differing meanings.

In this scene from the last act of Tennessee Williams' play The Glass Menagerie there are several places where changes in "thought actions" occur, places where an editor might logically make a cut. In the scene that precedes this speech, Tom, the narrator, has stormed out of the house, vowing never to return, swearing he'd fly to the moon before enduring another moment in his mother's home. He stands on the landing of a fire escape now, high above the stage, and tells the audience what happened:

"I didn't go to the moon, (1) I went much further (1a) for time is the longest distance between two places (2) Not long after that I was fired for writing a poem on the lid of a shoe-box. (3) I left Saint Louis. I descended the steps of this fire-escape for a last time and followed, from then on, in my father's footsteps, (4) attempting to find in motion what was lost in space (5) I traveled around a great deal."

Cuts could come at any of the numbered points. Whether to cut at (1), (1a) and (4) depends largely on how the speaker phrases the speech, and on his intention in communicating. Is the phrase "for time is the longest distance between two places" a stand-alone statement, a bit of philosophy; or does it modify " I went much further" and belong with that part of the speech? How you decide to cut will alter the sense or meaning of the scene.

Whether to cut at all is an even more interesting question. Film schools and video production courses often teach that long scenes are boring. Presumably audiences can't listen for long periods of time without visual distraction or they'll become bored and fall asleep. Yet in this example, Tom is telling a story, a story we have never heard before. Perhaps it would be most effective to let him tell it without interruption, just eyeball to eyeball, like story tellers of old. The speech is about three minutes long: why not hear it to the end, without interruption? To see how effective this strategy can be, look at how editor Frederic Knudston cut the railroad platform farewell scene between Ava Gardner and Gregory Peck in Stanley Kramer's On the Beach, and how Martin Scorsese filmed the famous "through the restaurant" scene in GoodFellas

Learn to trust the material. Don't cut unless it's necessary. Cut to physical action by all means, but remember that "thought" actions may carry much of the meaning of the sequence and that a cut in the wrong place can completely change the meaning of a scene. And remember that montage is always a factor in cutting. Sequences of cuts are never meaning-neutral. Finally, given the choice, cut rather than dissolve. You'll speak with authority and clarity in the language of video, and your voice will be heard above the rest.

For additional reading on the subject: Selected Takes, by Vincent LoBrutto and Walter Murch's In the Blink of an Eye,

Joseph V. Mascelli's The Five C's of Cinematography, and David Morgan's interview with editor Thelma Schoonmaker.